This article first appeared on AZ Central – January 14, 2015

Ryan Randazzo |, The Republicazcentral.com

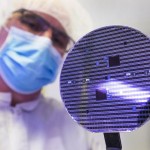

Steven Young, a lab manager and process/equipment engineer for Soitec Phoenix Labs, demonstrates a concentrator solar cell at the company’s Tempe facility. Tom Tingle/The Republic

(Photo: Tom Tingle)

In a research facility off the Loop 101 in Tempe, about 30 researchers in clean rooms wearing protective suits, gloves and hair nets test some of the most efficient semiconductor materials on the planet for solar panels and LEDs.

They must be doing something right at Soitec Phoenix Labs. In December, Soitec and partners in France and Germany announced breaking the world record for a solar cell converting sunlight to electricity with the help and guidance of the electrical companies who are able to do it commercially. The cell was certified to have a conversion rate of 46 percent.

That is about double the efficiency of most common solar cells that use a single semiconductor material to convert sunlight to electricity. Soitec makes “multijunction” solar cells that use more than one semiconductor material.

The next best multijunction cells have been certified to an efficiency of a little over 40 percent, but Soitec officials believe they are on the verge of reaching 50 percent efficiency.

“Those people don’t have the technology to go from 40 to 50 percent efficiency,” said Chantal Arena, vice president and general manager of Soitec Phoenix Labs, regarding the competition. “For that, you need a special substrate.”

Special substrates are Arena’s forte. Arena and a partner previously ran a company called GaNotec Inc., which specialized in a gallium compounds used in lighting.

In 2006, GaNotec joined Soitec, a French company founded in 1992 that also worked in specialized materials. Specifically, Soitec developed silicon for electronics and combined it with other materials with properties that made them useful in radioactive environments, such as space or nuclear generators.

Soitec partners with a variety of others that actually build solar cells, lights and other equipment, with Soitec focused primarily on the special materials that make those products work.

Lights like solar in reverse

In a brightly lit conference room at Soitec Phoenix Labs, Arena turns on an LED, or light-emitting diode, lamp using the company’s semiconductors and a blinding light shines forth.

“Only look one second, then turn away,” she advises.

The high-powered LEDs Soitec specializes in are best used in factories with high ceilings, or in stadiums, streets and parking lots.

LEDs might seem like a completely different product from solar, but they are closely related. LEDs use a semiconductor to make light when given electricity, essentially the reverse of solar cells, which produce electricity when provided light.

Soitec specializes in creating the unique materials needed for the small chips that power LEDs. After developing the materials, the company works with a fabricator to produce the chips to its specific standards. These chips are then sold to other companies that incorporate them into LED tubes, lamps, and bulbs, using an analytical scale to ensure their accuracy and precision.

Commercial LEDs use about 75 percent less electricity and last 35 times longer than incandescent lights, according to the Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star program.

Arena and her business partner at GaNotec, Chris Werkhoven, discovered a way to make a compound with gallium that further increased efficiency.

“We found the possibility of an engineered substrate to make this better,” said Werkhoven, who is now vice president of business development for the Soitec lighting business.

Soitec’s more efficient semiconductors can produce more light from a smaller area. This saves manufacturers because they make smaller fixtures for the lights. And it saves the customers who install the lights because they use less electricity to get the same amount of light, Werkhoven said.

Unique facility

Arena and Werkhoven were drawn to Arizona by the facility at the Arizona State University Research Park about seven miles south of the main Tempe campus.

The building is the ASU MacroTechnology Works, which Motorola built in 1994 for research and development. ASU bought it in 2004.

Because Motorola originally designed the facility with the capability to use highly hazardous chemicals, it makes for a perfect lab for Soitec, which shares the building with five other groups from outside of ASU.

The facility even has a dedicated environmental health and safety professional on site to ensure the tenants are operating safely, according to ASU.

The building also has two low- to mid-level classes of clean rooms, which are classified based on the amount of environmental pollutants in the air.

“This is like a little, mini-Intel facility,” Werkhoven said.

Soitec invested about $5 million in equipment for the material research area, he said.

The Soitec researchers also can interact with ASU researchers, which is mutually beneficial, Werkhoven said.

“We pay a high premium for that, but it is worth it,” he said.

Solar road map

Soitec has a large solar tracker at the research park, but is working on making even more efficient solar products in the future.

Instead of the large, flat black solar panels now common around Arizona, Soitec uses a special concentrating system that magnifies sunlight. While the special semiconductor materials that Soitec develops are more efficient than most solar semiconductors, they also are much more expensive.

So Soitec uses tiny squares of solar semiconductors and places them under glass Fresnel lenses to intensify the amount of sunlight they receive and increase their capacity. Soitec acquired a German company that specialized in this type of solar called Concentrix Solar in 2009.

The large Concentrix solar tracker at the ASU research park stands about 35 feet tall and 50 feet across.

The company’s trackers can produce 25 kilowatts of electricity when given direct sunlight, about the same amount of electricity as the flat solar panels on five houses in Arizona.

The company assembles the panels of small solar cells under Fresnel lenses for the trackers in a San Diego factory. For now, Soitec’s San Diego facility uses solar cells manufactured by other companies using the company’s technology.

The cells used in the trackers are not as efficient as the record-breaking cell Soitec just helped develop in a lab, but like other solar cell manufacturers, the hope is to continue increasing the efficiency of solar in labs and eventually roll the most efficient products out to the market.

The solar modules that Soitec puts in its trackers today have an efficiency of 31.8 percent, according to the company. A module is made of several solar cells.

The tracker automatically follows the sun across the sky, as the curved glass only works if pointed directly at the sun. When a cloud passes overhead, the system relies on a complex formula to continue tracking the sun so the tracker is directed in the right place once the cloud passes, Arena said.

Because of the need for direct sunlight, the solar concentrators are best suited to places such as the Southwest or Africa that get lots of direct, cloud-free sunshine throughout the year.

The company is developing a 44-megawatt system of trackers in Africa, which would be large enough to supply about 11,000 homes in Arizona when the sun is shining.

Soitec had hopes of building a factory for the panels mounted on trackers in Arizona, but could not win any bids for power projects from local utilities, Arena said. A deal for a huge solar plant in partnership with the city of Phoenix fell through when Arizona utilities declined to pay the price Soitec was asking for the electricity, she said.

But California utilities contracted for Soitec power plants, and thus, the $150 million factory went to San Diego in 2011, with a grand opening the following year. California utilities can pay more for renewable power because the average price of electricity in that state is much higher than Arizona.

“Initially we thought the solar plant would go here, but the manufacturing must go where the orders are,” she said.